Angela Da Cruz

What should you do with you eyes?

Summary

This research explores notions of identification, physiognomy, and expressiveness in relation to faces. The practice is essentially based on photographic experiments and multiple printed materials, mostly in black and white or monochrome, as a way to structure, highlight and contrast the compositions. Drawing on the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari on faces called faciality (visageité), as well as the influence of the history of photography on modern consciousness, I investigate how faces communicate meaning. My research questions the possibility of fluid encounters with faces in a context of crushing expectations and oppressive directions for our bodies, especially while being a woman. As I only photograph my close female friends, these pictures evoke the proximity between young women and their restrained expressions. Always on the threshold of the intimate and the clinical, the photographic frame reminds the restrictive boundaries of the female condition. This collection of faces is composed of three layers referring to three different methods of representation used throughout this research: sequencing, covering, and instructing.

Key words: Faciality Expression Gesture Covering Physiognomy

Method 1: Sequencing

‘The face itself is redundancy. It is itself in redundancy with the redundancy of signifiance or frequency, and those of resonance or subjectivity.’ (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987)

If repetition is inherent to the assemblage and communication of faces, these minimal variations or frequencies offer a possible comparison and classification. Faces resemble others because they display minimal but sufficient adjustments that play out as necessary differences. They happen to communicate by sets of similar meanings and evocations. Through that process appears a collection of acceptable faces and expressions that form a succession of negligible changes, a typological classification. A harmless game where one’s spots the differences between faces. But the term redundancy also evokes the monotonous and dull representation of faces, and yet it looks like a necessary element of construction, an insight to dismantle the expressive machinery of faces.

attempts to escape the frame of the image

playful exhaustions of the potential postures

the body is be declined as a motif.

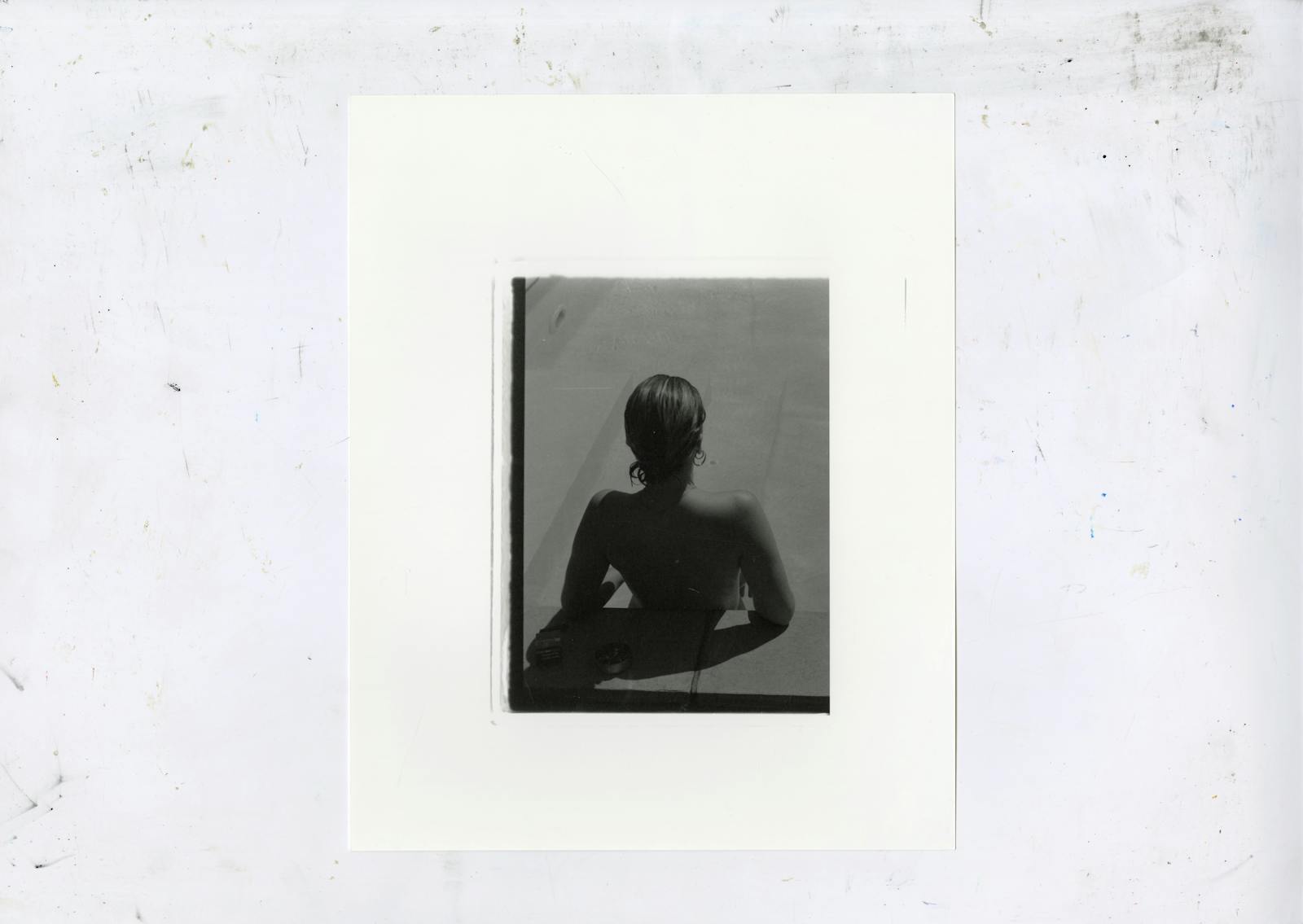

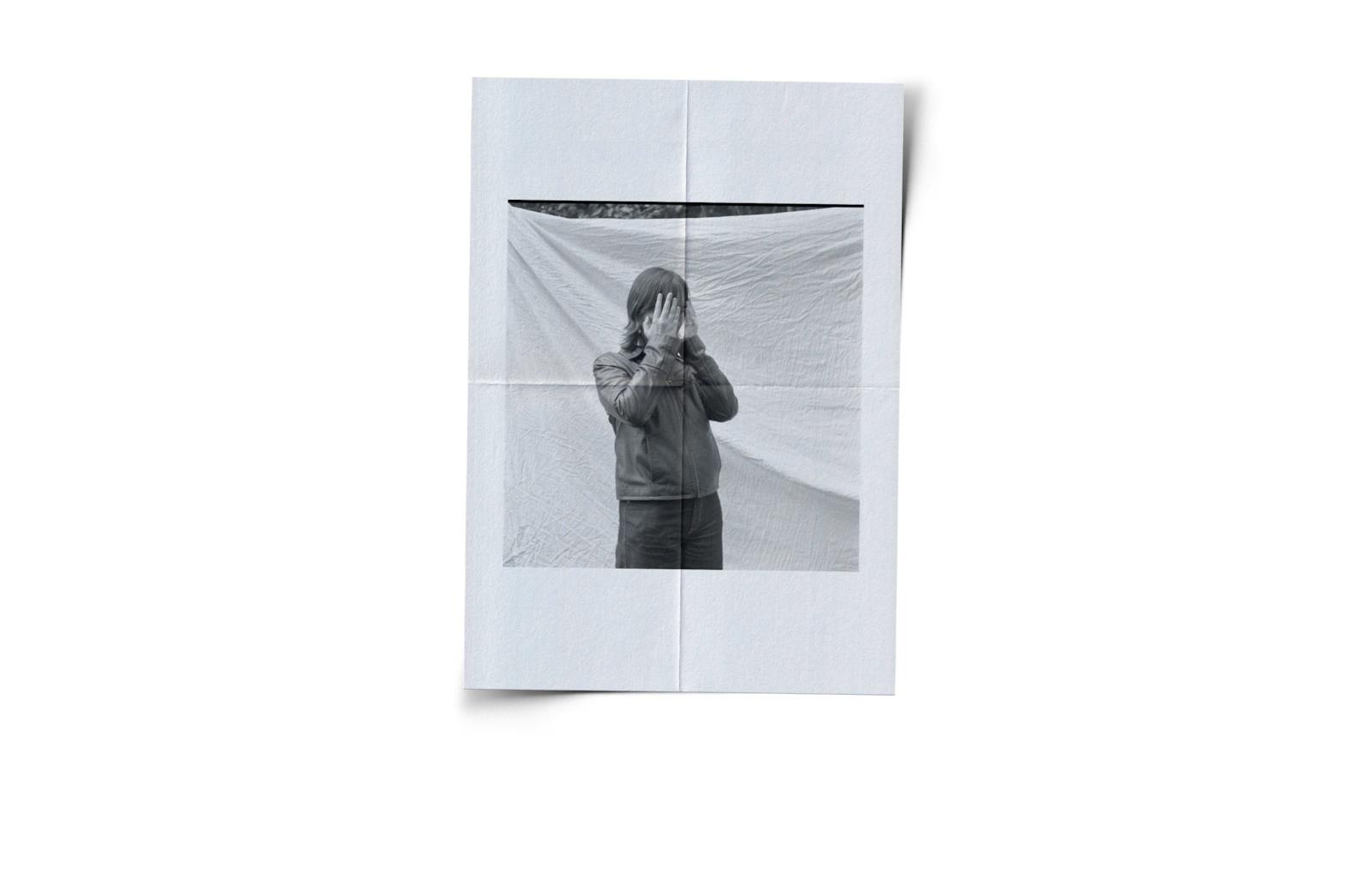

Working as the extension of these theoretical and visual references, I considered the initial structure of the negatives’ papers as a playful material for my subject to be sequenced in twelve images (when shooting with medium format). By revealing the process of photography, the printing of a contact sheet (fig.1) predicts a future selection, the need to choose the best image, and the most convincing face. In considering the materiality of the negative as a research process, it reveals a certain temporality between each frame as well as a certain imminence in fixing identities. This almost automatic choice underlines the unconscious approach to analog photography: a limited succession of images that should contain at least one successful representation. The structure of the contact sheet shows the authenticity and spontaneity of the creation process, a glimpse into pressing the shutter release. Multiplying the presence of the subject’s image ensures the permanence of the motif and reinforces the efficiency of faces’ communication. Addressing the process of darkroom printing, there are three necessary steps including revealing, stopping, and fixing the enlarged image on paper. Before obtaining the ‘successful and final image’, the test strips show a gradation of the different exposure times. In between these progressive scales is hidden the proper exposure, the legible layer. As a collection of failed representations and missed attempts to communicate, all these ripped pieces of paper (fig.2) represent the archive of what could have become faces, the up-and-coming fragments of significance. The process of failure plays out as a research method. If the face is a major element of identification, the photo booths’ prints (fig.3) precisely use successive frames as a method to provide a clear depiction of faces. The formality of the exercise lies in the linear sequencing of the photographic strip, and the redundant variations of portraiture. The face appears four times in a mugshot style while setting a specific cadence and allowing the existence of a latent space between each pose. A methodic redundancy that works as a rhythmic representation. These small identity documents are also pocket-sized objects or images that can be carried around. In considering the handling nature of these photographs, I also experimented with folding my prints as a direct surgical intervention on them (fig.5). The choice of the image is significant because it is a silhouette cropped from a negative (fig.4), initially set in a detailed background. In tearing away this figure from its context, it now appears as a timeless and suggestive appearance. The imprints testify that the image was held, folded, and potentially slipped somewhere. The left marks show clear and clean sectioning of the initial figure and create a grid when unfolding the paper. This sectioning reframes the initial image and gives the impression that the silhouette is in the viewfinder of that fold, threatened and targeted. By playing with these two different sizes of enlargements, the image of the silhouette slides along the folds like guiding rails. The small one and the large one are next to each other, they appear as redundant twins, implicit narratives. Sequencing is a methodical approach to photography and works as a measuring scale and a pacing element. It allows the structuring of a redundant element within a fragmented frame of representation.

Method 2: Covering

‘And why would a part of the body, chin,

stomach or chest be more partial, more

spatiotemporal and less expressive than

an intense feature of faciality or a reflexive

whole face?’ (Deleuze, 1986)

Elaborating on the obscure part of faces that Deleuze and Guattari call the black hole, there is clearly something that exceeds the common understanding of communication, an obscure inability to fully interpret a face. There is a possibility to divide faces up into different zones of significance: they have sad eyes, they are smiling, etc. But the black hole is relevant because it absorbs, swallows the potential clarity of faces, and establishes a lingering doubt. Faces are not more expressive because they are completely unveiled, they are just more familiar and reassuring. On the contrary, one losing control of their appearance can be manifested by an unexpected demonstration of expressions and emotions. The frightening and unstable face is said to be ‘naturally a close-up, and naturally inhuman, a monstrous hood’ (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p.190). This is dedicated to the methods of covering as an attempt to control the over-flowing tendency of faces, but also to reveal another dimension of expressiveness.

the piercing power of faces to express and their ability to appear even when they are covered.

the covered face calls for imaginary narrations and personal interpretations

an oneiric image and an eloquent ghost.

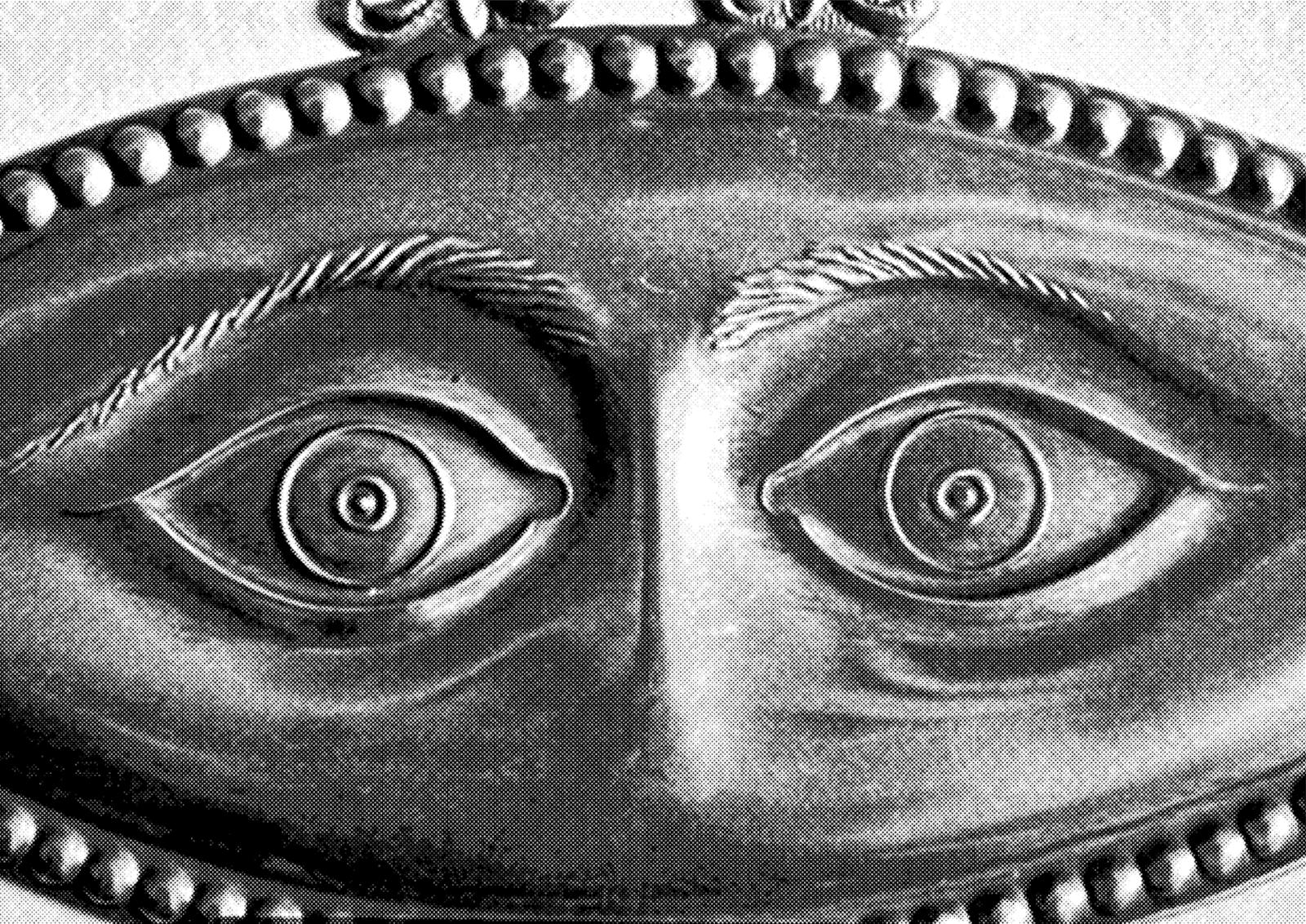

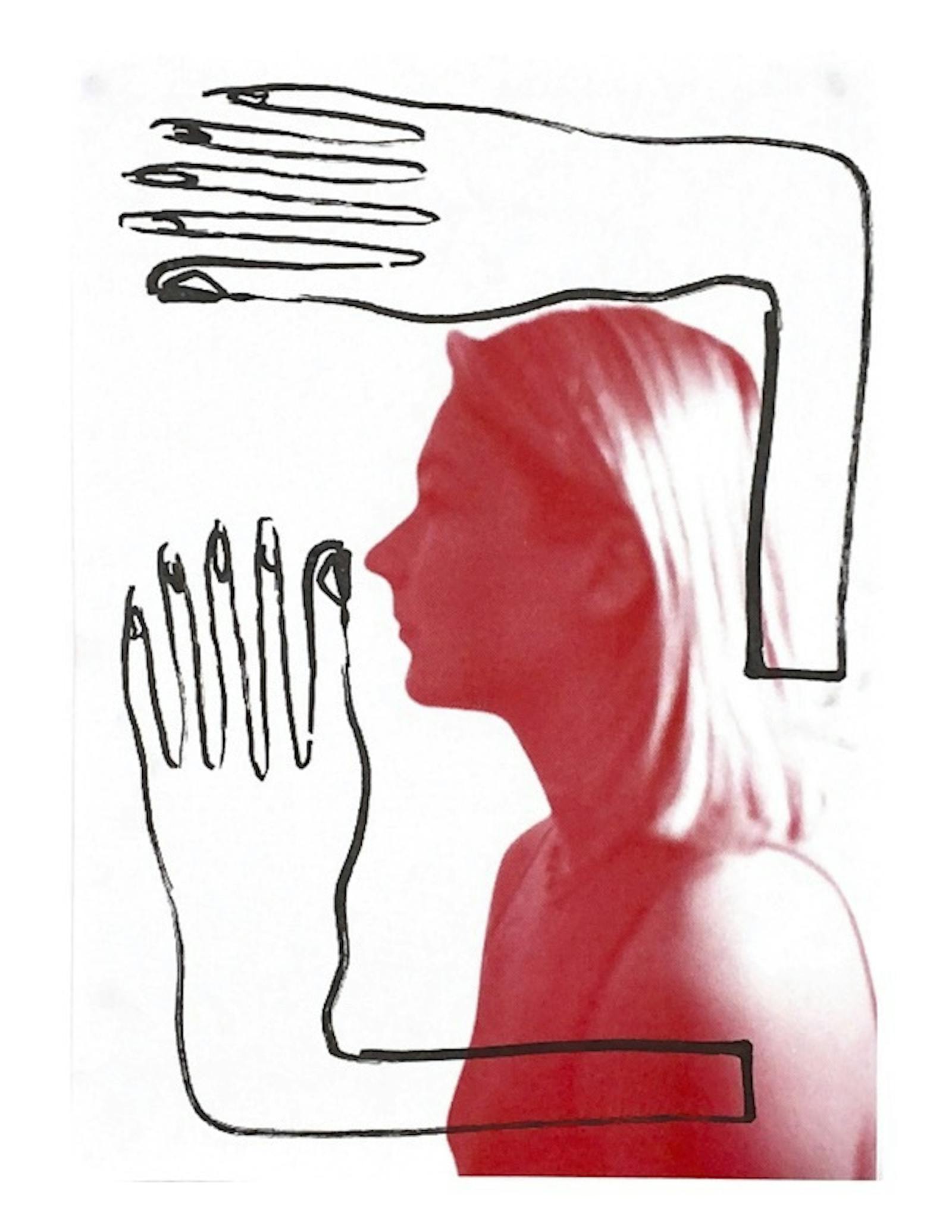

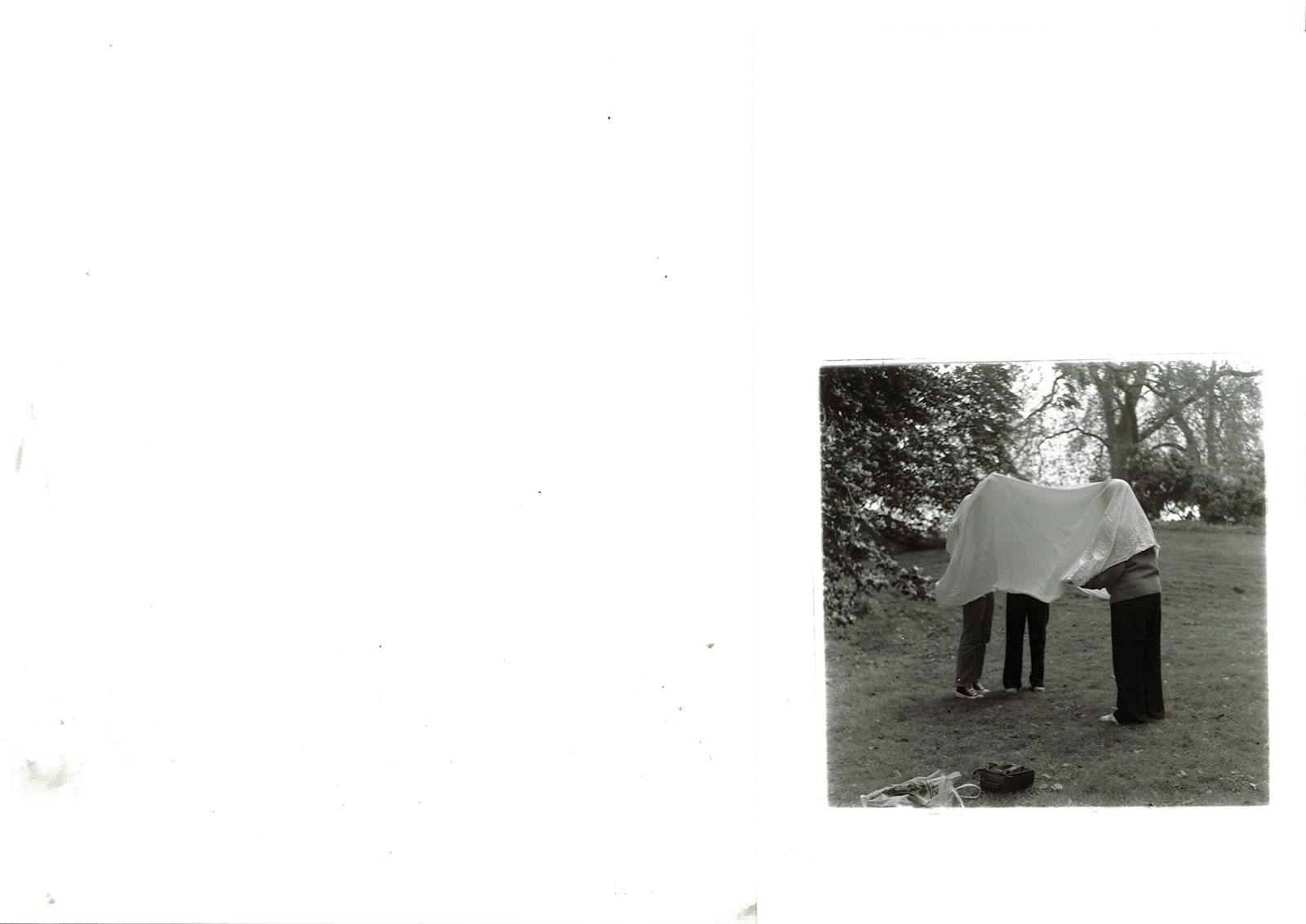

The covering was first translated into my practice through the out-of-focus portrait (fig.6). The use of black and white brings out a highly contrasted image and creates a chiseled portrait in which the outlines are clearly demarcated. If the shape is sharply defined, the inside remains an obscure and illegible surface. The absence of field depth in the image reinforces the collage impression while dismissing any contextual integration. Pursuing the idea of flattening the image as a method to conceal faces’ reliefs, this darkroom-printed photograph was developed into a risograph (fig.7). This mass-production printing technic combines two visual layers in one final print. In this copy, the face has been cut out from the initial photograph and replaced together with hand drawings. These two images both exist on the same plane and have been evenly covered by the dotted inking of the printer. While the use of red shows the face as an impended representation, the hands work as rough imprints. They rearrange everything at the forefront of the image and break with the depth impression of photography. The hands then became a repetitive motif and a covering method in my photography practice. They address the power of gestures in relation to facial expressions. In this series of photographs (fig.9, 10), the woman goes from a concerned gesture and questioning face to hiding behind her hands. What is she looking at? The juxtaposition of the two images can evoke various narrations of what happened between the opening and the obscuring. It could be sorrow or fear— this movement remains fluid because it continues the hands’ re- quest in the first photograph. This gesture of protection evokes Jacques Lacan’s concept of ‘radiated reticulation’ he explained with these words: ’In so far, as I am under the gaze, Sartre writes, I no longer see the eye that looks at me and, if I see the eye, the gaze disappears’. When soliciting a gaze, one does not gain the recognition of the other but rather a self-introspection of their own, a look back at themselves.‘I see only from one point, but in my existence I am looked at from all sides.’. The gaze is felt as an omnipresent and invisible force where faces are covered in a refusal to be stared at. As a universal experience, a collective cloaked face takes the shape of a six-legged ghost (fig.12) in one of my images. Because eyes have the power to petrify, the Medusa, because they become a symbolic authority. The covering of the face evolved into the display of a printed image of an ex-voto (fig.11). These traditional and devotional offerings often take the shape of stamped tins that serve as religious tokens. This form of folk art uses very literal representations to express the object of the vow, for example, a leg-shaped plaque for limb paralysis. In my photograph, the model holds the image of an eyed ex-voto at the back of her head. She holds her mask as an alternative representation of her face: two large carved eyes. Are they a protective device or the petrified result of being gazed at? The burden of having a face seems to be digging into all covering alternatives to provide a bearable existence for faces, to soothe expressiveness from faces’ hegemony.

Method 3: Instructing

‘This machine is called the faciality machine because it is a social production of

face, because it performs the facialization

of the entire body and its surroundings and

objects.’ (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987)

Encompassing more than heads themselves, faciality has the

power to spread through all available surfaces and impose its

codes. Preventing any disruptions to happen, the face is maintained in an obedient state and patiently awaits instructions. Because they are easily influenced and molded, faces reproduce

taught and learned expressions. They expect other faces to operate in radial symmetry so that every facial section would belong

to the overall model. When symmetry is not applied, identification occurs with rejection. ‘A defendant, a subject, displays an

overaffected submission that turns into insolence’. The overtaking is therefore seen as transgression. The body equally gives

in to instructions and becomes an extension of the face where

gestures and postures are compliant with the regime. In other

words, a hand movement or the shape of an object can express

as much as a face. This chapter examines what communication

system this instructive set of signs establishes. From this per-formative guidance appears a whole sub-language of refusal, a

whole imagery of the concealed.

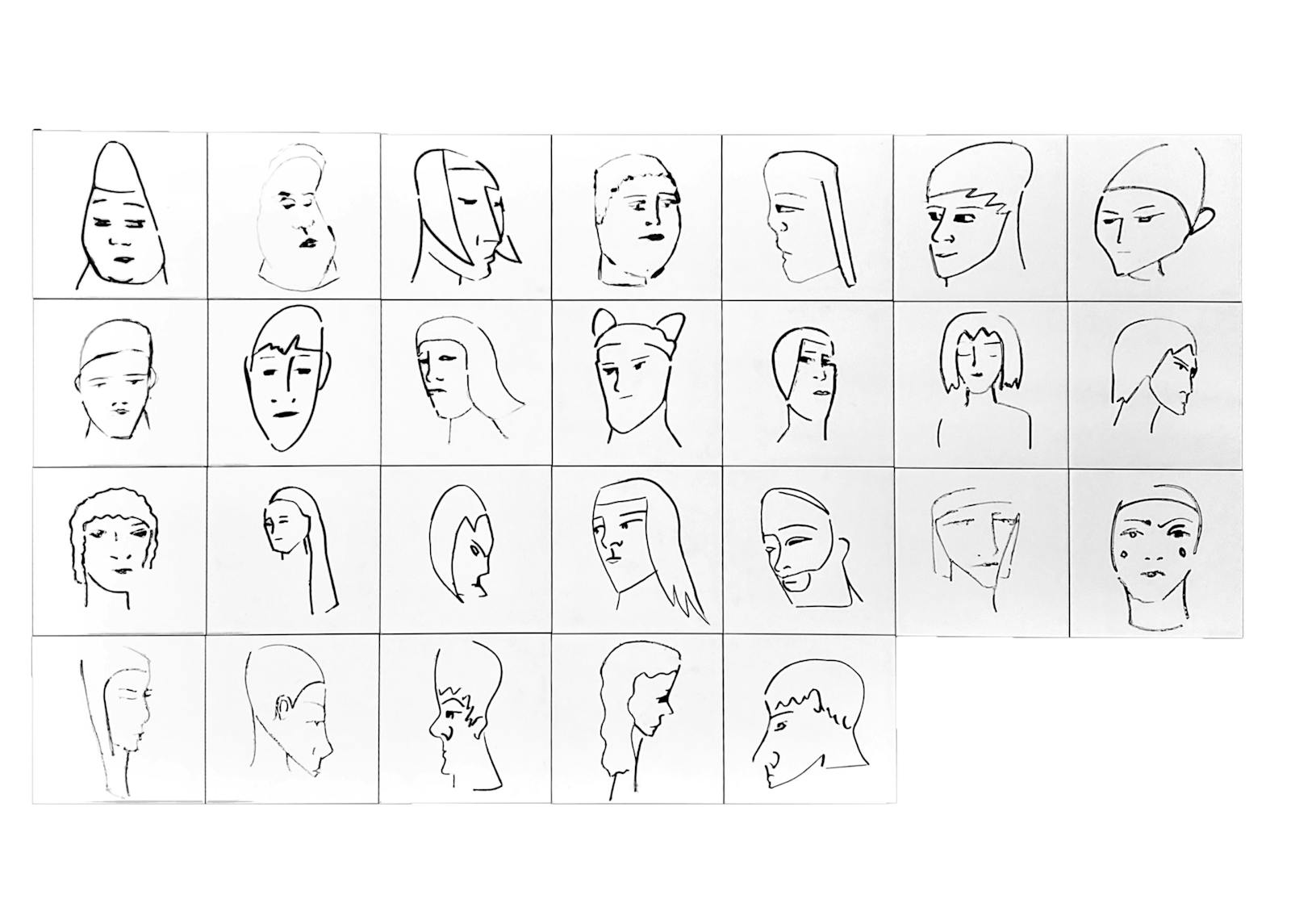

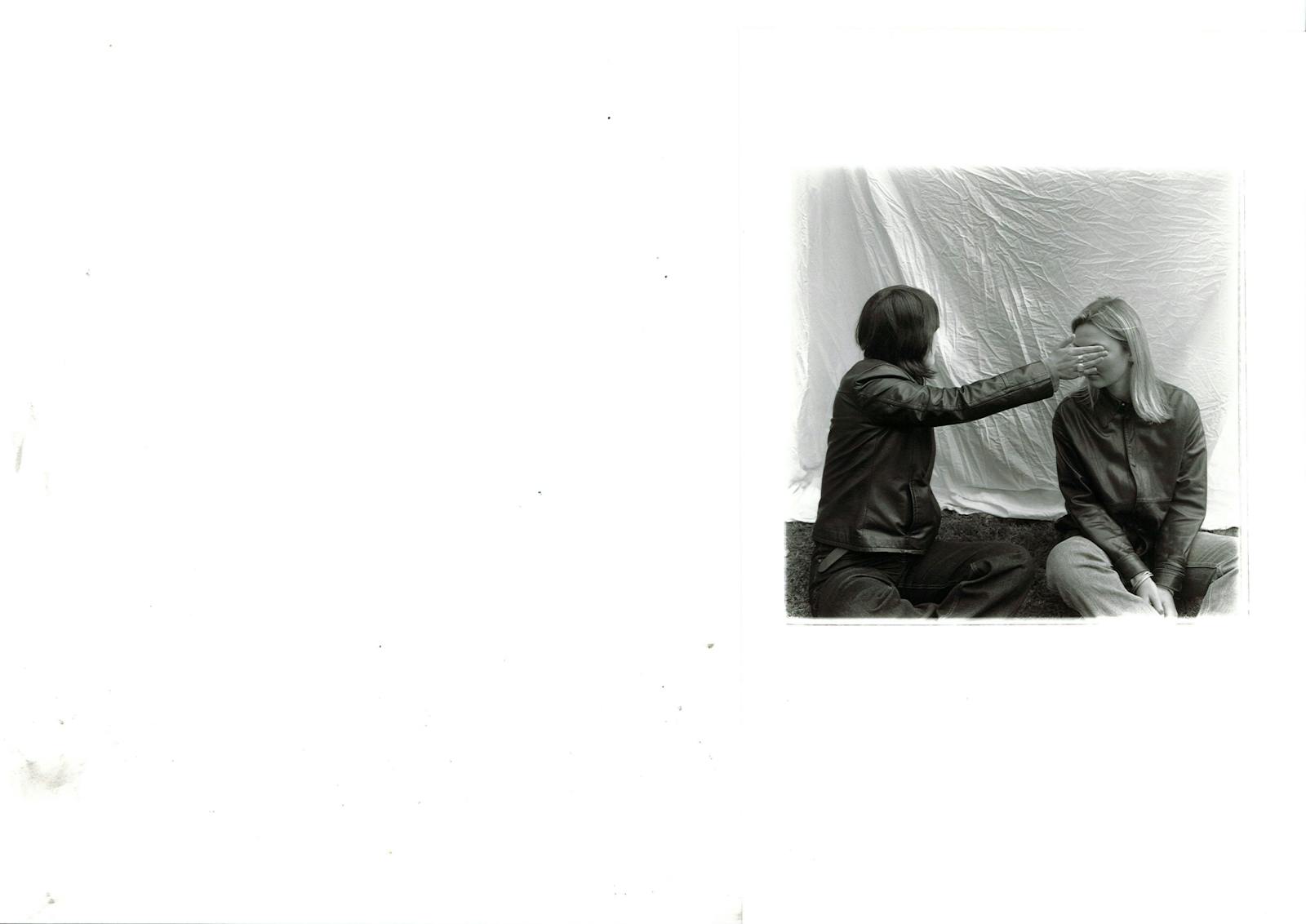

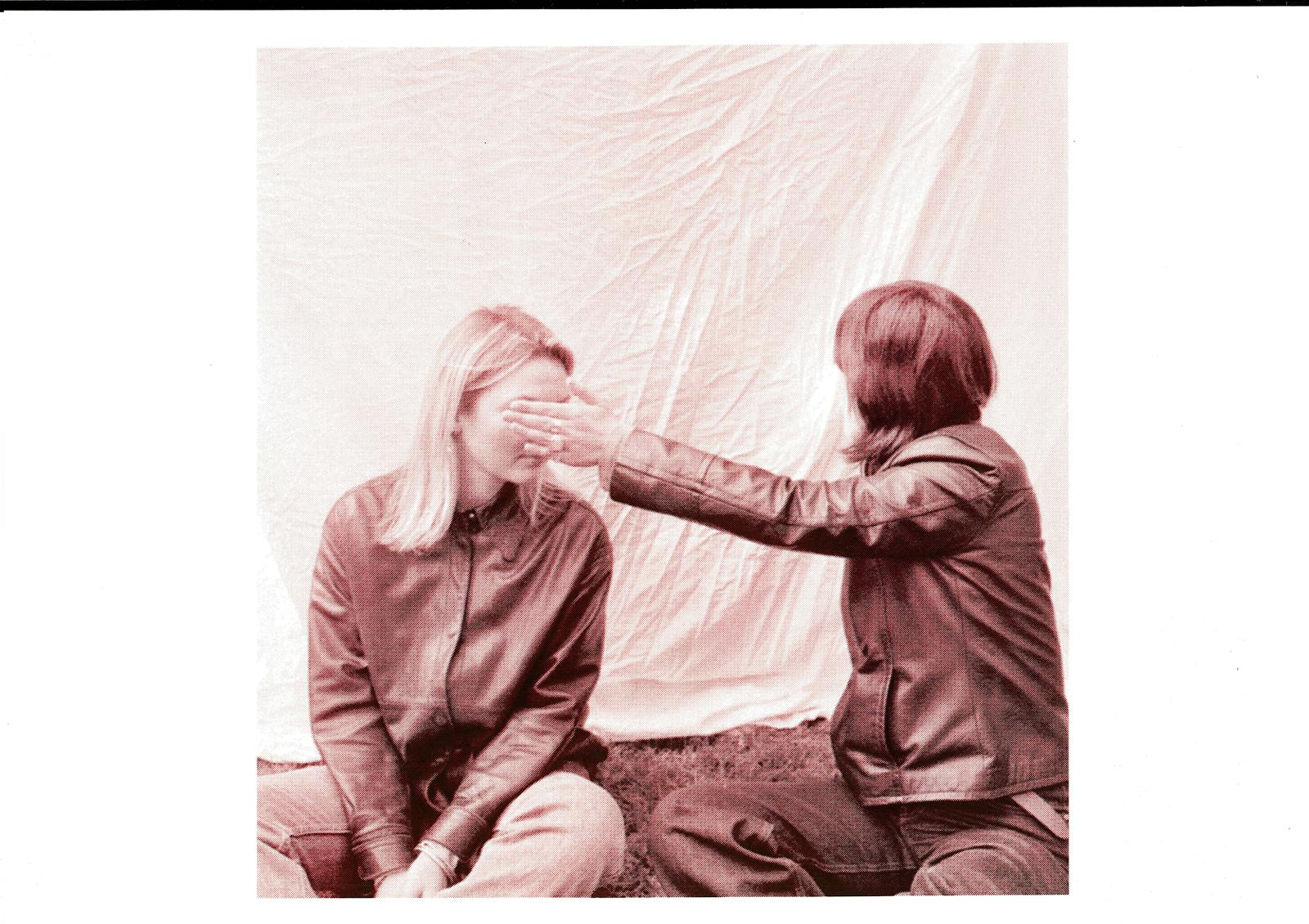

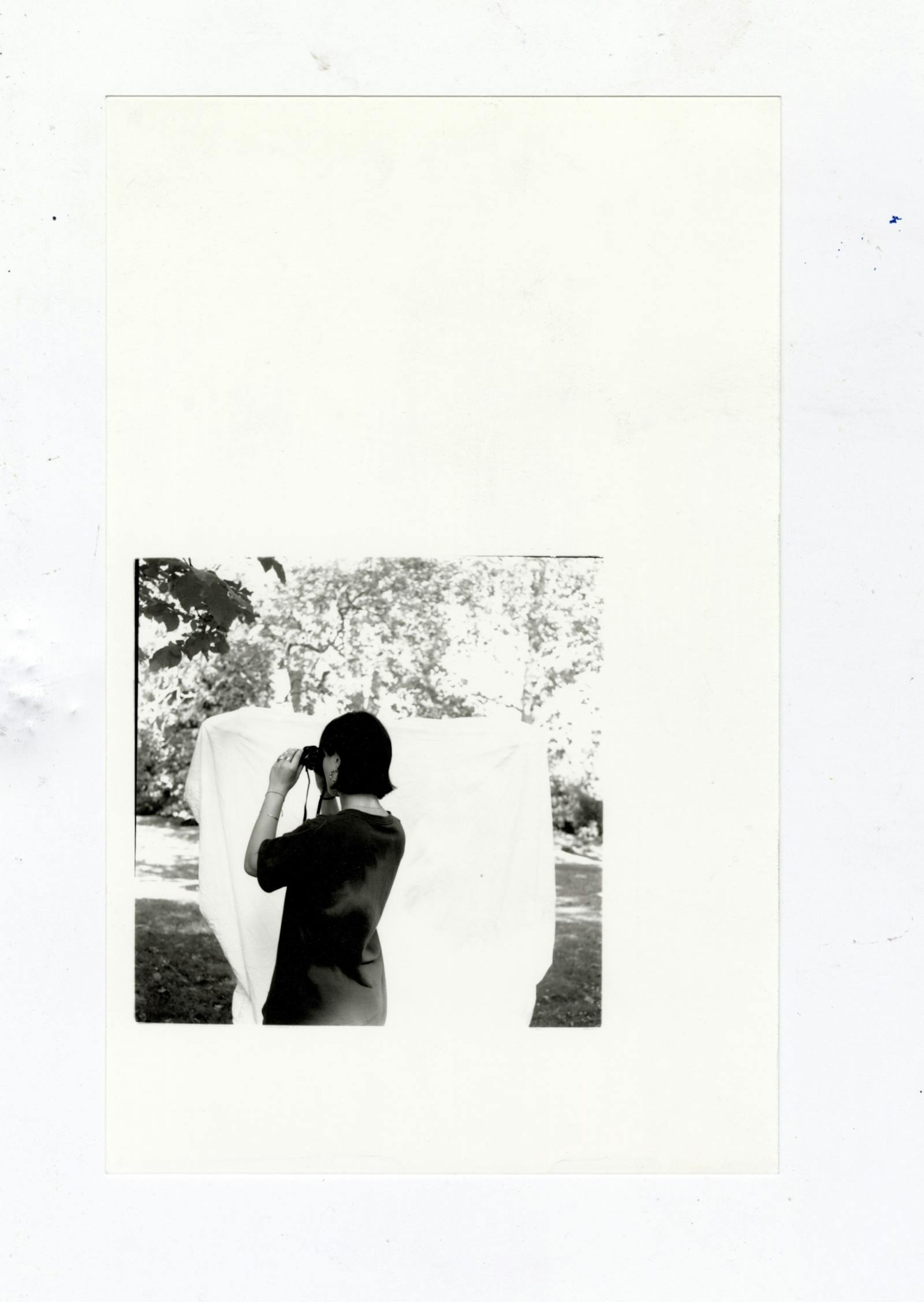

As a response to the expectations for fluid communication and obedience, I developed the ‘Iconographic Alphabet’ (fig.13) which is a set of twenty-six faces each replacing an alphabet letter. This visual alternative questions how firmly we rely on these systems of signs to communicate. Each face is an out-lined sketch inspired by the letter’s initial shape and plays out as a playful restructuring of the alphabet. Altogether, they form a confusing iconography, unfamiliar letters we cannot distinguish from one another. In this hypothetical writing system, the drawn faces would compose our words and sentences working as significant symbols. The ‘Iconographic Alphabet’ provides a variation of these inflexible codes. If the implementation of these systems should ensure fluid communication, it also reveals our expectation for others to use them properly. Faces expect clear expressions that serve as guidance on how to react in return. When not misled, a mirroring dynamic is set between faces as they tune into the other’s expressions as mutual decoding. Taken in front of a white sheet as the background (fig.14), these photographs depict a formal framing focusing on the models only. The woman is turning her head away from the camera while she is covering another woman’s eyes. By serendipity, they happened to be wearing a similar jacket which emphasizes the twinning impression of this image. The mirroring of the couple is even more relevant taken in the context of instructing and mimicking expressions. his gesture of complicity materializes the invisible presence of the gaze. In compliance with the other, the blond girl accepts the gesture. They are both aware of the camera’s eye and they consequently avoid its inquisitive intrusion. This photograph was also developed into a riso print (fig.15) which changes the perspective of the gaze and creates an interesting inversion of the initial image. The attempt to picture a dialogue between the visible, the invisible, and the concealed. If the gaze is intrusive, it can also be deflected. The photograph with the binoculars (fig.16) plays with a subversive redirection of the gaze. The woman is looking where the viewer cannot see: beyond the frame of the photograph. While the viewer is looking at this small print, the woman in the image is focused on a hypothetical remote object. Through her own lenses, she gazes into a magnified dimension. These different scales support the distance set between the viewer and the model but also question who plays the role of the observer. In this mise-en-abyme, the woman might be looking at the same image. Or she might be pretending to watch over, staging her surveillance. Because that is precisely what our faces and bodies are instructed for, to be ready and presentable for the insatiable gaze coming ‘from all sides’.

Visuals

Method 1: Sequencing

fig.1

fig.2

fig.3

fig.4

fig.5

Method 2: Covering

fig.6

fig.7

fig.8

fig.9

fig.10

fig.11

fig.12

Method 3: Instructing

fig.13

fig.14

fig.15

fig.16