What about this statue problem of ours?

Summary

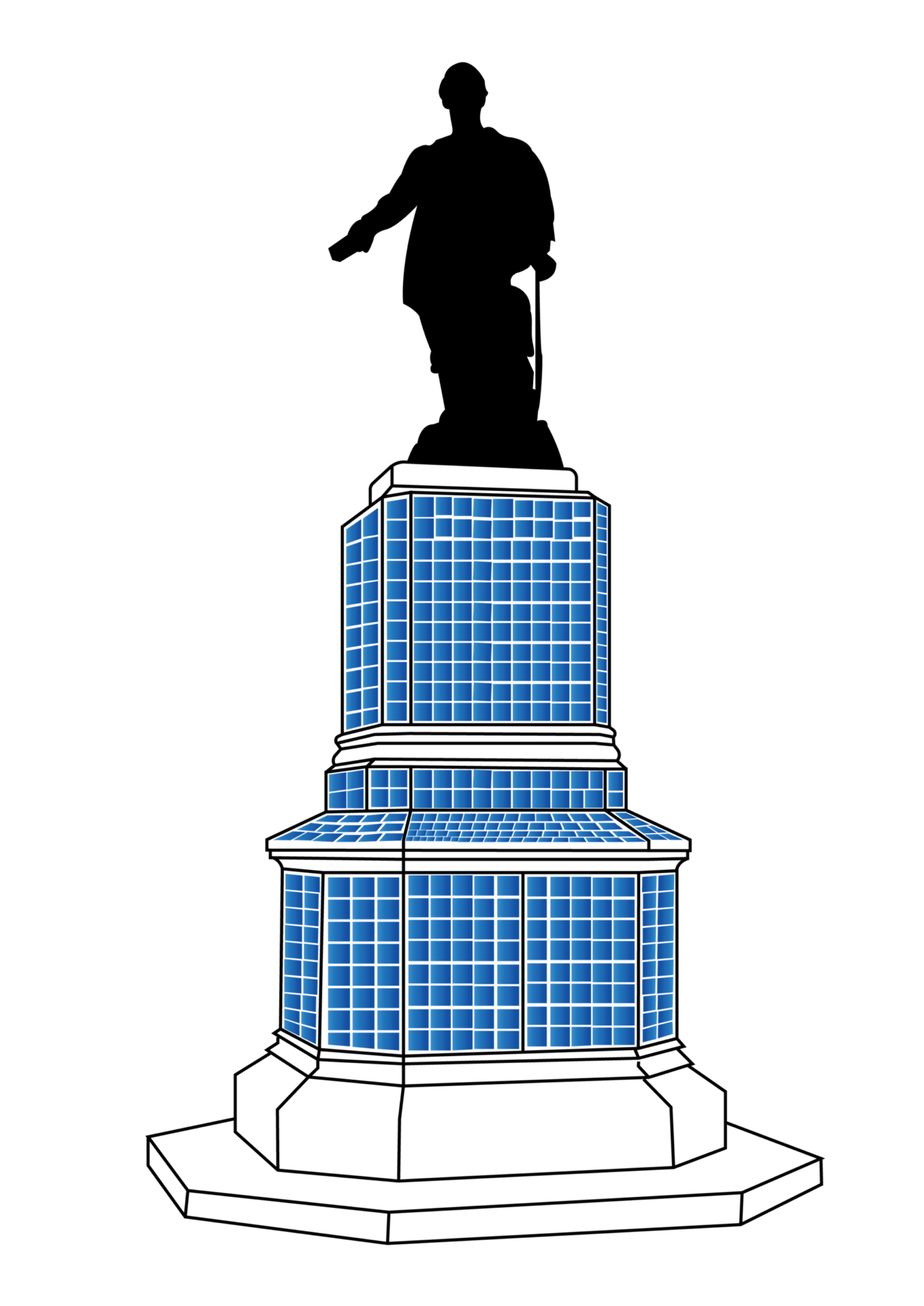

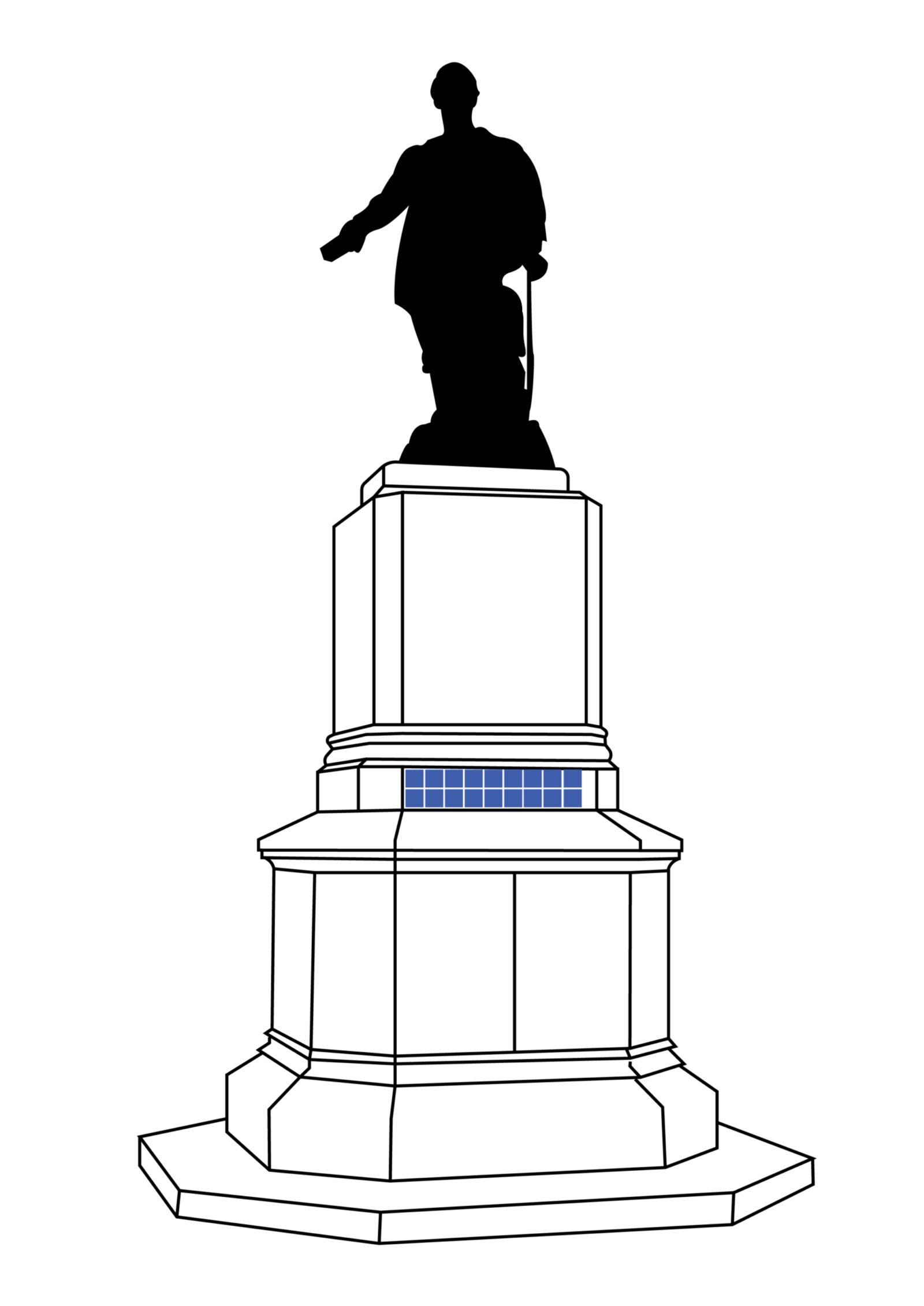

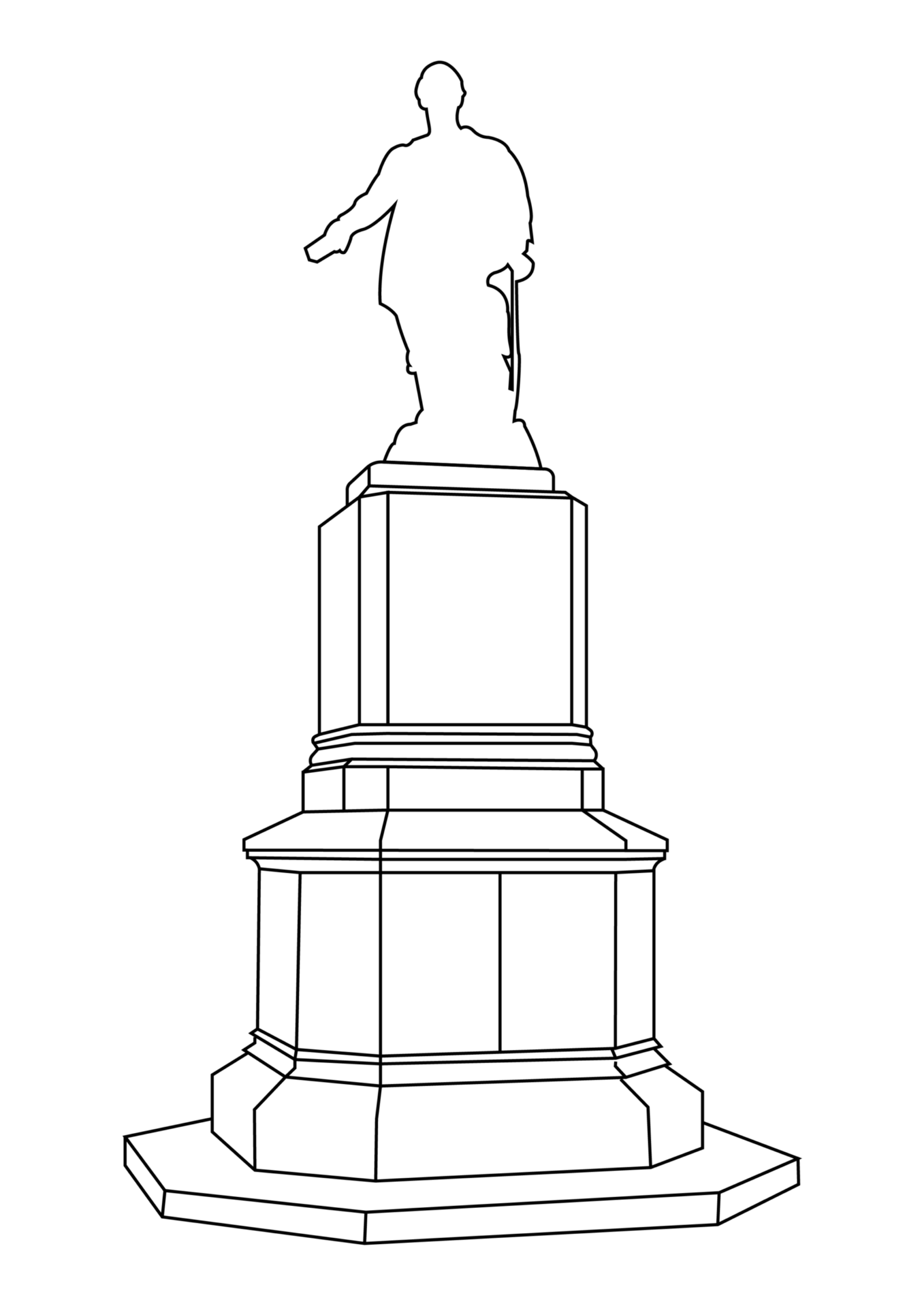

This practice-based research explores how shared heritage can be made explicit in public space by engaging with monuments as contested sites of memory. Focusing on the statue of David Livingstone in Edinburgh, Sechele Mtitimila installed tiles—featuring portraits of African soldiers from the King’s African Rifles—at the base of the statue. These men, drawn into World War I under British command, directly challenge Livingstone’s narrative of Christianity, Commerce, and Civilisation. The work reimagines the plinth as a palimpsest —a layered surface where counterhistories can emerge.

Drawing on Stuart Hall’s question “Whose heritage?”, alongside hauntology and the politics of memorialisation, this project proposes a framework for design-led overlays that build upon rather than remove colonial monuments. By collaging new narratives into old foundations, the work invites critical reflection on Britain’s national identity and its enduring entanglements with empire, transforming fixed statues into evolving visual prompts for engaging with contrasting perspectives on imperial history beyond the conventional frames of gallery walls and museum displays.

Additional info

"It strikes me that the idea of tiling this statue is more radical than the actuality. It’s what the idea represents rather than the physical act. In the context of Britain’s rigid heritage protection systems, even minor alterations to listed monuments are highly regulated and subject to lengthy bureaucratic processes. Within this framework, the notion of building onto—rather than removing or preserving— represents a design intervention that challenges the assumed permanence and singular authority of heritage."

This title, What About This Statue Problem of Ours?, borrows its rhetorical shape from a mid-20th-century tradition in British broadcasting, where programs posed —“Would you let your daughter marry a Negro?” or “What about this colour problem of ours?”—to a presumed white audience. Today, a similar national anxiety surrounds the fate of imperial monuments and statues across the UK. Far from being neutral markers of heritage, these statues serve as enduring symbols of empire and selective historical memory.

In 2020, statues became a focal point in the so-called culture war when a statue of Edward Colston—a Bristol merchant who amassed his wealth through the transatlantic slave trade—was pulled down and thrown into Bristol Harbour during a Black Lives Matter protest.

The same year, Winston Churchill’s statue in London was defaced with graffiti reading "racist," prompting far-right figure Tommy Robinson to mobilise supporters to protect national monuments as part of a "defend our memorials" campaign.

In 2023, during far-right riots on Armistice Day, some attendees, concerned about a potential race war, claimed, “Armistice is our day”, asserting they were there to protect monuments.

To deface, destroy or remove public property can be understood as an act of dismantling power—an attempt to seize control over the narratives that dominate shared spaces. Yet it can also be seen as a kind of erasure—removing or obscuring the uncomfortable truths of the past, potentially sanitising history rather than confronting it. These are often acts of anger and frustration—responses to systems that are perceived as failing the people they claim to serve.

The above text contains extracts from the thesis: What about this statue problem of ours? Heritage, Empire and a Designer's Intervention in Urban Space